Explorers’ Epic Journey: Lewis and Clark's Role in America's Westward Expansion

The 1803 territorial acquisition that doubled the size of the United States was more than a land deal; it was a strategic bet on a nation’s destiny. In a purchase orchestrated to secure political and economic leverage, the United States acquired a sprawling expanse from the Kingdom of France, transforming a continental boundary into a crossroads of opportunity. By absorbing roughly 2 million square kilometers of river systems, plains, canyons, and coastline, the young republic unlocked a corridor for exploration, commerce, and national identity. The purchase, valued at a modest sum per square kilometer by modern accounting, set in motion a chain of events that would shape everything from cartography to diplomacy, and from migration patterns to regional development.

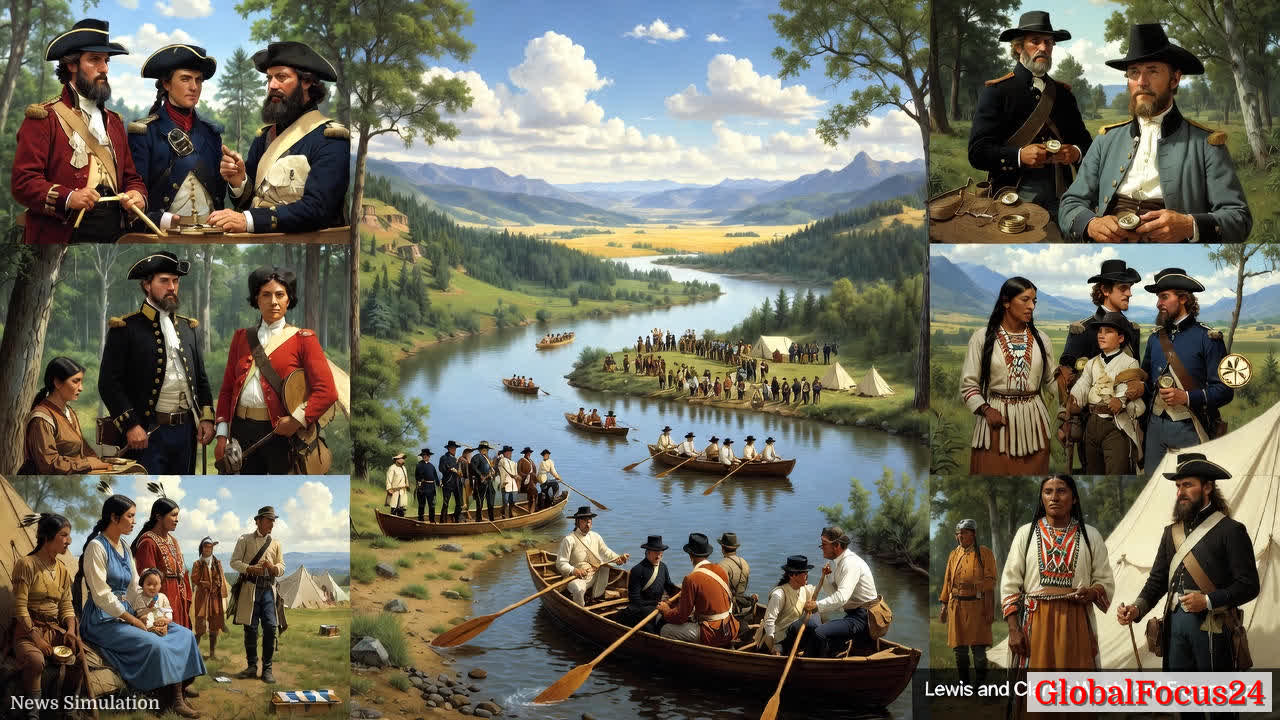

This watershed moment in American history culminated in one of the most celebrated expeditions in the annals of exploration: the Corps of Discovery, commanded by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Begun in May 1804, their mission extended beyond a mere trek westward. It was an ambitious attempt to chart unknown waters, establish diplomatic relations with Indigenous nations, and ascertain whether a viable water route to the Pacific Ocean could unify a continental empire. The journey began near the gateway city of St. Louis, where more than forty souls, bound by hunger for knowledge and curiosity about distant landscapes, faced a strenuous ascent against the Missouri River’s current.

Historical context underscores the expedition’s magnitude. The United States stood at a crossroads, balancing agricultural expansion, commercial ambitions, and the imperatives of national security. With European powers eyeing North America’s vast interior, the Lewis and Clark voyage emerged as both a scientific mission and a strategic assertion of sovereignty. The Corps’s diaries, journals, and maps offered a window into the continent’s hidden geographies, yet they also carried the weight of implications: how would a nation manage relationships with Indigenous peoples whose lifeways, economies, and territorial rights intersected with every mile of newly acquired land?

The early phase of the journey tested resilience and leadership. The group faced harsh weather, scarce supplies, and the arduous realities of long-distance travel. Illness and disease, elements of risk in any expedition, took a toll, with Sergeant Charles Floyd’s death in August 1804 marking the expedition’s sole fatality. Yet the expedition’s cohesion endured, aided by disciplined camp routines and a pragmatic approach to provisioning and resource management. The men learned to improvise, to navigate with limited navigational tools, and to rely on the landscape’s rhythms—timber, game, and water—as primary navigational and sustenance sources.

Diplomatic engagements with Indigenous communities formed a central theme of the voyage. Encounters with the Oto and Teton Sioux tested the expedition’s diplomacy and restraint. A tense standoff, averted through patient negotiation, demonstrated the power of diplomacy in reducing friction on the road to national objectives. The mission’s strategy for navigating intertribal relations balanced curiosity with respect, aiming to foster peaceful interactions that would increase the likelihood of safe passage and collaboration.

The journey’s most enduring symbol of cross-cultural diplomacy emerged in the partnership with Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman whose presence—along with her French husband—helped secure the expedition’s forward momentum. Sacagawea’s role extended beyond companionship to practical diplomacy: her knowledge of local routes, her pregnancy, and her ability to guide the party through unfamiliar territories lent an aura of peaceful intent to the group’s arrivals in new villages and camps. The infant Pompey, Sacagawea’s son, became a potent emblem of goodwill and non-threat in a landscape characterized by suspicion. The narrative note that “who carries an infant on a war party?” later underscored the expedition’s strategic messaging: peaceful intent can be as persuasive as force.

As the corps pressed westward, the terrain intensified. The group confronted Montana’s treacherous river corridors, including the formidable Great Falls, a landmark that tested endurance and ingenuity. Crossing the Rocky Mountains proved equally demanding, with steep passes and severe weather shaping the expedition’s pace and provisioning. Starvation, dysentery, and cold conditions sharpened the group’s resolve, while interludes of negotiation and cooperation with Indigenous horse traders and guides opened new routes and possibilities. The reorientation provided by new allies—most notably Sacagawea’s Shoshone kin—offered essential resources, including horses and local knowledge about traversing high-altitude landscapes.

The expedition’s official entry into the Pacific Coast in November 1805 marked a dramatic milestone. In less than two years, the Corps had traversed more than 6,600 kilometers (roughly 4,100 miles) from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, a feat that redefined the geographic imagination of the United States. Their arrival did more than yield a scenic achievement; it produced a data-rich corpus of observations: notes on flora and fauna, weather patterns, river systems, and practical guidance for future settlers. Of particular note are the 122 new animal species documented during the journey, including grizzly bears and pronghorns, along with detailed descriptions of plant life and ecological interactions. These field notes offered invaluable data for later agricultural development, resource management, and scientific inquiry.

The expedition’s impact extended beyond scientific and geographic revelations. It accelerated the tempo of westward migration, transforming a remote frontier into a region of sustained, organized expansion. Settlers, traders, and policymakers looked to the Lewis and Clark narrative as a blueprint for bridging vast distances through rivers, trails, and riverine networks. Rivers, in particular, emerged as conduits of unity and commerce: the Missouri and Columbia systems offered practical pathways for transport and integration into national and global markets. The diaries and maps produced by the expedition helped to lay the groundwork for a unified national narrative—one that tied economic potential to geographic discovery, and that framed the West as an arena for opportunity rather than merely a boundary to be defended.

Economic implications of the expedition’s legacy are multifaceted. The data gathered—ranging from resource inventories to potential route optimization—contributed to rational planning for infrastructure, settlement, and defense. The prospect of a continuous corridor linking the interior to the Pacific facilitated downstream investment in trade networks, agricultural development, and regional specialization. The expedition also influenced policy directions in the nascent United States: a clearer understanding of river routes and landforms informed decisions about fortifications, territorial governance, and the allocation of federal resources to support exploration, settlement, and defense.

In the broader regional context, the Lewis and Clark journey can be read against the backdrop of a growing continental economy. The Pacific Northwest would later emerge as a nexus for timber, fishing, and maritime trade, while the upper Missouri Valley became a cradle for cattle and agricultural production. Across the breadth of the trans-Mississippi West, communities gradually aligned with the broader national economy, integrating Indigenous knowledge, settler entrepreneurship, and federal policy to shape development trajectories. The expedition’s influence thus rippled through successive generations, contributing to a dynamic pattern of regional growth that would ultimately knit the tapestry of a continental United States.

The narrative also invites reflection on the expedition’s human dimensions. Personal challenges, including Lewis’s struggles with alcoholism and Clark’s complex relationship with York, an enslaved individual who faced his own constraints, illuminate the social and moral complexities that accompany frontier ambitions. These elements remind readers that historical accounts are nuanced and contested, inviting ongoing examination of the human stories woven into the fabric of exploration. The moral landscape surrounding these episodes prompts careful consideration of how society remembers, interprets, and learns from the past, particularly in relation to enslaved persons and their roles in national narratives.

From a long-term perspective, the Lewis and Clark expedition stands as a landmark in American exploration, a model of disciplined inquiry, logistical coordination, and cross-cultural engagement. The project’s success did not erase conflict or tension on the ground; instead, it reframed such tensions within the broader calculus of national growth, security, and economic opportunity. The expedition’s enduring value lies in its systematic documentation, its demonstration of coordinated teamwork under challenging conditions, and its role in shaping policies that encouraged inland settlement while acknowledging the strategic significance of river basins and coastal access.

In reflecting on regional comparisons, historians often contrast the Lewis and Clark voyage with other exploratory missions of the era. While many expeditions pursued shorter-term goals, the Corps’s trek spanned seasons, landscapes, and cultures, producing a durable record that could inform both immediate operations and long-range planning. When comparing the Pacific Northwest’s development with other frontier regions, the expedition’s emphasis on river-based mobility, resource mapping, and tribal diplomacy emerges as a recurring theme in shaping successful and sustainable expansion. The enduring lesson is that exploration, when paired with rigorous documentation and collaborative engagement, can yield tangible benefits for a nation’s economic architecture and strategic posture.

Public sentiment during and after the journey varied, reflecting the broader tensions of a nation in flux. The sense of wonder at reaching the Pacific and witnessing previously unseen biomes inspired awe and admiration. Simultaneously, exclamations about potential opportunities carried undercurrents of fear and opposition from communities whose lands and ways of life would be affected by deeper settlement. Modern readers may encounter vivid reminiscences of early frontier optimism paired with the sobering recognition of displacement and conflict that followed in later decades. This duality—admiration tempered by caution—serves as a reminder that national narratives are rarely monolithic and that the history of expansion includes both achievement and consequence.

Looking forward, the Lewis and Clark legacy continues to inform contemporary understandings of geography, infrastructure, and cross-cultural collaboration. The expedition’s emphasis on rigorous observation and data collection provides a template for modern scientific and logistical missions, whether those efforts focus on climate research, watershed management, or transregional commerce. The West’s 16-state expanse, ultimately linked by river corridors and road networks, stands as a living testament to the expedition’s early vision: a connected, prosperous republic defined by mobility, resourcefulness, and a willingness to learn from diverse partners.

In sum, the Lewis and Clark journey embodies a foundational moment in American history, one that reframed how the United States would interact with its vast interior. It demonstrated that careful preparation, disciplined leadership, and open engagement with Indigenous communities could transform a perilous expedition into a catalyst for enduring economic and geographic integration. The expedition’s records—maps, journals, and observational notes—remain valuable assets for researchers, policymakers, and citizens seeking to understand how exploration translates into national growth. As the nation continues to navigate the legacies of expansion, the Lewis and Clark narrative endures as a compelling chapter in the story of American resilience, ingenuity, and ambition.